Brendan Fraser plays a morbidly obese teacher who is facing imminent death while trying to reconcile with his angry teenage daughter.

Brendan Fraser plays a morbidly obese teacher who is facing imminent death while trying to reconcile with his angry teenage daughter.

For those who might not appreciate nuance, The Whale could seem like a misleading title. Charlie, the main character played by Brendan Fraser, is a morbidly obese English teacher living in a small house in Idaho, confined both by his enormous size and his deteriorating health. His friend and nurse, Liz, has told him that he has congestive heart failure and maybe only a few days to live. But he refuses to go to a hospital.

The Whale does not refer to Charlie, but to Moby Dick, and specifically an essay about that novel that he has come to treasure. But the writer, Samuel D. Hunter, also wants us to associate this title with Charlie because one of the movie’s themes is the vicious and punishing attitudes that we see expressed towards people that are fat. And by this implication, the audience is challenged to see through those attitudes.

Charlie teaches essay writing to freshman college students online, and we see him on Zoom encouraging them to be honest and original in their essays rather than trying to imitate or follow a formula. But he doesn’t turn on his own camera on Zoom, claiming that it’s broken. Charlie doesn’t want them to see what he look likes and how he’s living.

A young Christian man who comes to his door to proselytize is from the same evangelical organization that Charlie’s partner Alan had been a part of, and gradually we learn that Alan had died in some mysterious fashion because the church had expelled him. This is another important theme: Charlie, you see, is gay, and as the young missionary becomes a major character in the story, the film draws a crucial connection between religious fundamentalism and homophobia.

Watching The Whale, I could tell almost right away from the film’s structure that it must have originally been a play. All the action occurring in one place, five basic characters, a limited time span, the nature of the dialogue, all were clues as to this origin, and sure enough—in the end credits we find that Hunter’s script was adapted from his own play of the same name. The movie has some of the familiar limitations of filmed plays: schematic, implausible at times, speechifying, the sense that the action is carefully calculated. However, the director is Darren Aronofsky, who excels at amplifying extreme emotional states and taking us to the darkest depths of a person’s soul. In this case, we explore the depths of a man’s guilt, and luckily that man is played by Brendan Fraser, with a powerful and disturbing performance. He is the movie, essentially, and all the little flaws that you might notice in the story are as nothing in the aura of his presence.

Most troubling are the scenes where Charlie tries to navigate his little house in his ruinous state of health, and especially those where we witness his terrible eating disorder, the despair and trauma he experiences expressed through self-punishing bouts of gluttony. Hunter, and Aronofsky, want us to stop looking down on such a man and instead allow the awareness of his suffering to enter our hearts.

We eventually come to the center of Charlie’s drama—his urgent need to connect with his angry teenage daughter Ellie, played by Sadie Sink. She treats him with hatred and contempt, and yet he persists. All the strands of the story unite in a tension that starts to seem unbearable, and at the very height of that pressure, the film hits you in the gut. You can’t help but feel it. The Whale is a nightmare, a tragedy, and an incredible catharsis.

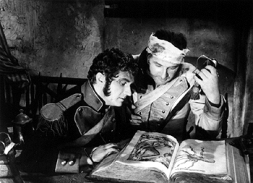

The Saragossa Manuscript, a 1965 film from Poland directed by Wojciech Has, became something of a cult favorite among younger American moviegoers at the...

Jean-Pierre Melville, a French director who loved America and its cinema so much that he changed his last name to that of the author...

For your Halloween pleasure this year, I offer the 1943 film I Walked With a Zombie. It’s from the famous horror unit at RKO...