The Seventh Seal was Swedish director Ingmar Bergman’s seventeenth film, made in 1957, and it was the first to propel him to international fame. It’s easy to see why. A film of intense, dreamlike imagery, it surprised audiences with its conviction that religious and philosophical questions can be handled powerfully in a motion picture.

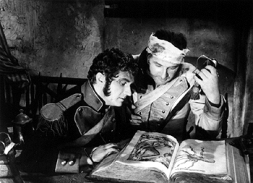

Here’s the story. Surrounded by the ravages of the plague, a medieval knight (played by Max Von Sydow), who has returned home from the Crusades, is confronted by the personification of Death (played by Bengt Ekerot) whom he challenges to a game of chess. As the knight wanders the country with his squire (Gunnar Björnstrand), who is a bitter atheist, he struggles with doubt about God and life, encounters a wandering circus troupe that includes a gentle fool (Nils Poppe) and his wife (Bibi Andersson), and all the while continues his dialogue, and his chess game, with Death.

The movie presents a kind of medieval world of the mind, boldly translating a grief-haunted theology into stark visual terms. The spooky look of the film (from wonderful black-and-white photography by Gunnar Fischer), the over-powering sense of the Middle Ages as a strange time of cruelty and suffering, the remarkable set pieces such as the procession of the flagellants through the village—are all combined to create an effect that was different than anything audiences had seen since the days of German expressionism. Even the quieter moments of seeming contentment, such as the knight eating strawberries with the young couple from the troupe, have the ominous feel of a pause for rest in the middle of a fight to the death.

The plague, and the atmosphere of fear, turmoil, and madness in the film’s world, is a spur to the knight’s questions, namely: What meaning could there be in all this suffering? and, For what purpose does God allow all this? and of course, Is there even a God at all? The cynical attitude of the squire is the philosophical counterpoint to the knight’s quest (with Björnstrand turning in the film’s standout performance), while the various actions of the other characters represent people trying to survive and get along in one way or another.

Ultimately, Bergman’s philosophical concerns are conveyed more completely by the picture’s visual style and emotional texture than by the dialogue. Of course the images of the caped angel of Death, and his chess game with the knight, are now so familiar (to the point of being repeatedly imitated and even spoofed) that it’s difficult to see them with fresh eyes. But it’s well worth the effort to do so. With a receptive mind one recognizes the picture for the startling, original, and disturbing work of art that it is.

The Saragossa Manuscript, a 1965 film from Poland directed by Wojciech Has, became something of a cult favorite among younger American moviegoers at the...

Korean director Bong Joon-Ho presents a science fiction action adventure about a child’s bond with a super-pig, corporate greed, and the evils of factory...

Chris Dashiell celebrates his favorite films from last year. At the end of a year, film critics start putting out “Top 10” lists or...