A black family in south Florida deals with hardship and regret, in this remarkably poetic drama by Trey Edward Shults.

A black family in south Florida deals with hardship and regret, in this remarkably poetic drama by Trey Edward Shults.

I just saw a film that touched me deeply, a movie playing at the multiplex for which I had not seen any ads or trailers. It’s about a fairly affluent African American family in south Florida, parents with a son and daughter, and some painful and dramatic things they go through. The name of the film is Waves, and I guess the title is partly due to the ocean, which plays a part in a romance depicted early in the film, but it may also refer to the waves of feeling that flow through you when you experience drastic and unforeseen changes.

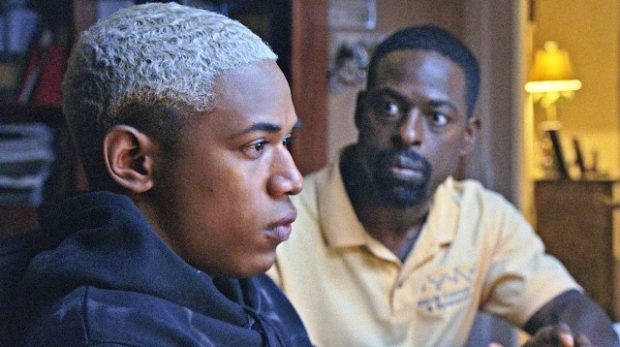

The son in the family, 18-year-old Tyler, played by Kelvin Harrison, Jr., has striking good lucks accentuated with bleached-blond hair. He’s a star athlete on the high school wrestling team, in love with a beautiful girl, and with a bright future ahead of him. But a shoulder injury puts his entire season in jeopardy. A doctor tells him he has to stop wrestling and get surgery. But he doesn’t tell his parents about this.

His father, played by Sterling K. Brown, is strict and dominating. He is in fact in charge of Tyler’s training, and pushes him hard to achieve excellence. The reasoning is a common theme among black Americans—you need to work ten times harder to achieve success in this white society. Dad is an authoritarian, although it’s clear that he loves his son and wants the best for him. Evidently, Tyler is afraid of his dad’s disappointment, so he hides his condition, taking pain pills to get through the meets. Then his girlfriend tells him she’s pregnant. This added pressure really sets him off, until the tension starts to come to a boiling point.

The writer and director of Waves is Trey Edward Shults, who had some success with a couple of relatively low budget films. With this one, he’s become more confident and ambitious. The average filmmaker might just focus on Tyler’s story, getting as much dramatic mileage out of it as he could. But Shults does something very unusual. At the climax of Tyler’s storyline, he gently shifts the film to his younger sister Emily, played with grace and sensitivity by Taylor Russell. Emily’s journey may not be as tumultuous as Tyler’s, but the feelings are just as strong, and Shults explores her emotional terrain with a combination of intense close-ups and an immersive style expressing her experience of exquisite beauty in the world that surrounds her. She goes on a trip with her boyfriend, played by Lucas Hedges, and is able to keep a sense of boundaries while being open to his feelings, and ultimately his grief.

Race is only mentioned once in the film, although it’s naturally displayed as a background to the life of the family. More important for Shults is showing how much hard work must go into reclaiming the respect and love within the family that events threaten with despair and ruin. The filmmaker has taken a big chance here by expanding his story outward into a place of thoughtfulness and integrity, rather than simply depicting conflict. Like a refining fire, the film’s sadness and grief, endured and come through, produce a stronger and more patient love.

Jordan Peele’s horror film, about people encountering their murderous doubles, has a dark social critique underlying its frightful surface. Jordan Peele has followed up...

Julian Schnabel’s portrait of Vincent Van Gogh, beautifully portrayed by Willem Dafoe, focuses on the subjectivity of a painter for whom art was the...

The Saragossa Manuscript, a 1965 film from Poland directed by Wojciech Has, became something of a cult favorite among younger American moviegoers at the...