A young black man yearns to reclaim the old San Francisco house that he grew up in, but which his father lost, in this film about home, friendship, and the city by the Bay.

A young black man yearns to reclaim the old San Francisco house that he grew up in, but which his father lost, in this film about home, friendship, and the city by the Bay.

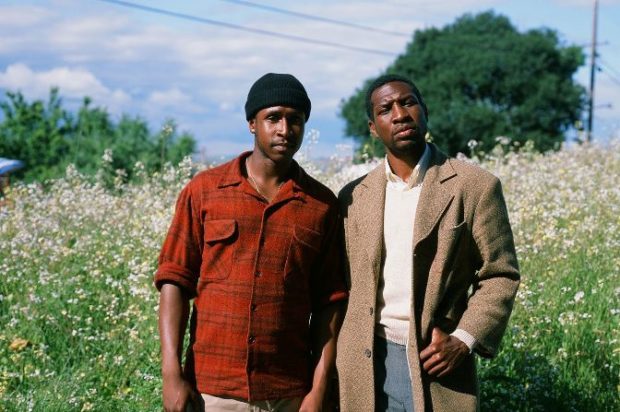

A new film tells a beautiful, tender story about a house and a friendship. It’s director Joe Talbot’s first feature, entitled The Last Black Man in San Francisco. The tale concerns a young African American man named Jimmie Fails, who plays a version of himself in the film, and who dreamed up this story with his old friend Talbot when they were teens. How much of it is strictly autobiographical I don’t know, but the fact that Fails has the same name as his character tells us that this is an intimate personal film.

Jimmie grew up in a beautiful old house in San Francisco, with an ornate Victorian architectural style that includes a little tower topped with a roof in the shape of a witch’s hat, as they call it in the film. His father, a bit of a shady character, lost the house somehow, and now Jimmie comes and gazes at it with melancholy longing in the company of his best friend Mont, a brilliant aspiring playwright. When the current residents are out, they go on the property and trim the hedges, weed the garden, even paint the trim on the windows, until the owners catch them in the act and tell them to leave.

Jimmie lives with Mont and Mont’s blind grandfather, played by Danny Glover. A group of street characters regularly gathers on a corner outside, playing the dozens, a constantly escalating game of verbal insults; and these guys, at least in the mind of Mont the eccentric playwright, represent a kind of Greek chorus to the main action. Jimmie finds out that the house’s owners have moved out, and that there’s some inheritance dispute preventing its sale, and so he decides to break in and squat there, which he and Mont promptly do. The inside of the house is, if anything, more beautiful than the outside. The film chronicles the struggle to somehow win back Jimmie’s childhood home, while interrogating the idea of home itself and the emotional bonds created by the places in which we’ve grown up.

The film’s title, The Last Black Man in San Francisco, is of course not meant literally, but in the sense of how Jimmie feels. African Americans used to own fine old homes in the city, but as time went on, black families were priced out of their neighborhoods, in a process we refer to now as gentrification. Jimmie feels as if he’s the last black man to make a claim to these old neighborhoods in San Francisco, and Talbot evokes the strange and lovely atmosphere of that city, in scenes which display both humor (as when a nude man sits down at a bus stop next to Jimmie, and it’s treated as completely normal) and gentle pathos (as in the opening sequence featuring a young black man preaching to nobody in the middle of the street).

Talbot co-wrote the screenplay with Rob Richert, and one of the film’s many triumphs is the character of Mont. As played by Jonathan Majors, Mont acts a bit “off,” maybe somewhere on the autism spectrum, but his loyalty to Jimmie, and his commitment to telling the truth, are deeply moving. Their friendship seems intensely real, the obvious love between them tinged with a sense of loss. Ultimately, though, it’s Jimmie’s love for the house that must be tested. His dream must come to terms with the reality of his story. The Last Black Man in San Francisco is a film of deep and abiding emotion, and it’s one of the best movies I’ve seen so far this year.

Ari Aster’s disturbing drama about a man (Joaquin Phoenix) who is afraid of everything all the time, bursts through the limits of the horror...

The true story of a large Romanian family living in a wilderness area facing the threat of being forced to move to the big...

Terrence Malick returns to his position as one of the greatest living film directors in this true story of an Austrian farmer who refuses...