Wes Anderson’s playful new film is presented as an issue of a Paris-based American magazine, with three stories about the eternal appeal of non-conformists.

Wes Anderson’s playful new film is presented as an issue of a Paris-based American magazine, with three stories about the eternal appeal of non-conformists.

Wes Anderson has a style that is decidedly his own and no one else’s. Those of us who follow his work are familiar with his toy-like production design, bright colors, block-like movements and set ups, eccentric stories and characters, and obsession with detail. His latest is called The French Dispatch, which is the name of a fictional weekly magazine, a foreign affairs supplement to an American newspaper in Kansas, of all places. The Dispatch itself, however, is published in a small French town, and edited by a grouchy, avuncular oddball played by Bill Murray. This is all just a framing story. The movie itself is presented as if it were an issue of this magazine, with an introduction, three feature articles, and an end note. The lightness of the premise, in a story anthology form instead of the usual long single narrative, allows more freedom for Anderson’s silliness. We know that he loves silliness, but here he really doubles down on his comic view of human beings and their struggles. I think it takes courage to be this silly, this willing to throw caution and plot believability to the winds in the service of laughter.

The three main sections are in black-and-white. I think it was a kind of dare to do this, to demonstrate that Anderson (and his longtime cinematographer Leonard Yeoman) can achieve striking beauty without color. The black-and-white puts a new emphasis on Anderson’s sense of pattern and space. This version of the world as a series of mazes and tunnels, to be observed through windows and precarious angles, becomes more striking without the distraction of color. On the other hand, the surrounding sections that are in color evoke a crucial difference between the printed word and the people creating it.

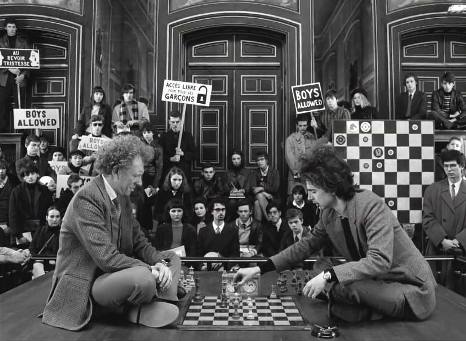

The first story is about an outsider artist, played by Benicio del Toro, creating his paintings in prison, who is discovered by an art dealer and impresario played by Adrien Brody, desperately and hilariously trying to promote the work, and himself. In the second story, Frances McDormand is a Dispatch writer who finds herself more intimately involved in the drama of a Paris youth movement headed by a young rebel (Timothée Chalamet) than she should be. The third features Jeffrey Wright, imitating the mannerisms of James Baldwin, as a food critic doing a piece on a chef, who instead ends up in the middle of a kidnapping story involving the son of a police commissioner played by Mathieu Almaric. All three stories reveal unexpected depths of meaning and rueful wisdom about life’s hard knocks.

The Dispatch is clearly meant to be a goofy tribute to The New Yorker, the American magazine with a long and storied literary influence. Anderson loves to make fun of the craft of writing, and the pretensions that always come to the fore, but it is an affectionate ridicule, which conveys a longing for the days when journalism was braver and more lively. I think he also loves the idea of having his own acting troupe—the picture is so full of famous actors that it can be distracting at times—oh look, there’s Henry Winkler, or Willem Dafoe, Saoirse Ronan, and many others in small parts. But it’s all part of the game. The French Dispatch may not be Wes Anderson’s best film, but it’s possibly his most playful.

The Wrong Box showcases a kind of inspired silliness exclusive to the British. There’s a special place in my heart for silly comedies. I...

A satire about a Black literary novelist who publishes a trashy book under a pseudonym to mock the way African Americans are depicted, only...

A daring debut film from Maysaloun Hamoud tells a story of Palestinian women living in Israel and defying conservative norms by choosing to live...