A new film from the West African nation of Ivory Coast presents an intriguing allegory about power and its misuse. Night of the Kings, the second narrative feature of Ivorian director Philippe Lacôte attracted critical notice, and won the Amplify Voices award for films from smaller countries at the Toronto Film Festival.

A new film from the West African nation of Ivory Coast presents an intriguing allegory about power and its misuse. Night of the Kings, the second narrative feature of Ivorian director Philippe Lacôte attracted critical notice, and won the Amplify Voices award for films from smaller countries at the Toronto Film Festival.

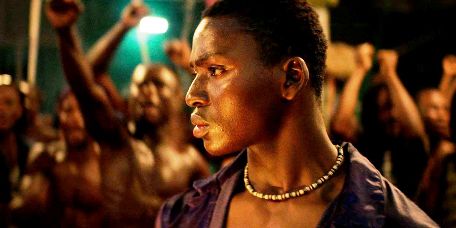

A huge prison in the middle of the rain forest has been abandoned by the state—the warden and his staff oversee the convicts from a sealed room, while the penitentiary is run by the inmates, a hell on earth in which only the strong and the cunning can survive. This society in miniature has developed its own political traditions. One inmate rules them all, but if he becomes unwell, the rules say he must take his own life. The current ruler is a burly old man nicknamed Blackbeard and played by Steve Tientcheu. Blackbeard is clearly ailing—he has an oxygen tank to help him breathe—and he knows there are adversaries trying to take him down. When he notices a new young inmate, played by Bakari Koné, being admitted to the prison, he decides to use him in a bid to gain time.

An old prison tradition says that during a period when the moon turns red, the ruler can declare a man “Roman,” or storyteller. The Roman must tell the gathered prisoners tales all night, or face death, and in the meantime Blackbeard will take steps to undo his enemies. If you didn’t realize that we were in the realm of myth before this, you will now with this fanciful but evocative narrative ploy. Immediately one thinks of the Arabian nights, and the framing story of Scheherazade, who must keep telling stories or face being executed by her tyrannical monarch of a husband.

As it happens, the moon appears red after a spectacular sunset, and the new Roman is called upon to start his tale. He says he doesn’t know how to tell stories, but when the inmates are all gathered, he nervously starts talking anyway. He tells of Zama King, a recently killed crime lord in the slums of the capital, a person everyone has heard of and whom he claims to have known. But realizing that he must talk all night, he invents a complex origin story in which Zama King was born and raised in a previous century, as a child in the pre-colonial era when a powerful queen ruled the land. Roman must stretch the story until daybreak, after which he will be safe from being killed.

The story expands to include multiple meanings, not least of which concerns the trauma of the recent five year civil war, which audiences in Ivory Coast would remember, but not foreign viewers. Never mind, the metaphor is relevant to all people suffering from the aftermath of war, and to all suffering under autocratic regimes like the one in the prison. In Night of the Kings, the modern and the mythic are one, reflecting the universal stories of power and corruption that plague mankind. The film is also a tribute to the tradition of the west African griot, the storyteller, poet, and musician who passes on the myth, history, and traditions of the people.

As Roman speaks, he is often accompanied by the songs, pantomimes and dances of other prisoners. And the film takes us away momentarily from the prison, as we are shown scenes from the drama of Zama King. As the dawn approaches, and Blackbeard’s enemies gird for the final struggle, Night of the Kings takes on the nature of legend, a national epic played out in the world of society’s most powerless members. This astonishing film confronts us with the fearful consequences of a society ruled by brute force instead of love.

Jia Zhanke’s saga of a woman finding the strength to survive after being abandoned by her small time gangster boyfriend, reflects the anxiety of...

Brendan Fraser plays a morbidly obese teacher who is facing imminent death while trying to reconcile with his angry teenage daughter. For those who...

The Act of Killing, a documentary film by Joshua Oppenheimer, starts us out with some very minimal historical background. In 1965, the government of...