A drama of a woman unjustly ostracized reveals deeper meanings, in a breakthrough work of Mexican cinema.

A drama of a woman unjustly ostracized reveals deeper meanings, in a breakthrough work of Mexican cinema.

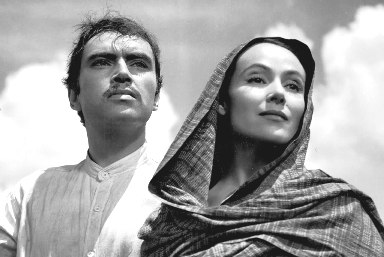

María Candelaria, a 1943 film by Emilio Fernandez, is a prime example from what is considered the “golden age” of Mexican cinema. The title character, María (played by Dolores del Rio), a young Indian peasant living in the river country of Xochimilco, has been ostracized by her village because of a scandal involving her deceased mother. She is loved by Lorenzo (played by Pedro Armendáriz), who hopes to marry her when they can get enough money, but they are in debt to a corrupt landowner who wants María for himself, and so tries to destroy them out of jealousy. Meanwhile an artist (Alberto Galan) from a nearby town who wishes to paint the beautiful María, tries to help the couple get out of danger.

The plot elements are pure melodrama, but the treatment raises the story to another level. The heroine represents a spirit of independence, freedom, and a love that is not cowed by custom or tradition. The villagers use ideas of honor and virtue to justify their own envy and hatred, and the film condemns hypocrisy in sexual matters as well, which was rather advanced for its time. Fernández and his co-screenwriter, Mauricio Magdaleno, cleverly wrap their social consciousness in the conventions of popular fiction—we instinctively identify with the downtrodden María and recognize the morality of the villagers as false. They also set up a dichotomy between the light-skinned ruling class and the Indian peasants, which must have struck a chord with Mexican audiences. The film was a major success at home, and won the top prize at Cannes, the first Latin American film to do so, and this helped foster a boom in Mexican cinema during the late 1940s.

Del Rio had been a Hollywood star for years—here she looks at least a decade younger than her actual age of 38. The part calls for sensitivity and nobility, and she comes through with flying colors. The acting in general is quite good, but the real reasons the film works as well as it does are Fernández’s fluid style and the photography of Gabriel Figueroa. The budget was miniscule by American standards, but Figueroa’s luminous black-and-white images lend the film a haunting, almost mythic grandeur. The camera movement has a calm, graceful rhythm. Fernandez also uses some striking point-of-view shots, as in a scene where we see Lorenzo from below as he rows down the river while María lies in the boat looking up at him. María Candelaria portrays the struggles and tragedies of the poor in a way that is affecting without becoming maudlin. The ending finally achieves something close to poetry.

The two most famous film versions of Victor Hugo’s novel featured Lon Chaney in 1923, and Charles Laughton in 1939. In 1831, Victor Hugo...

Getting old is the source of fear in a new horror movie by Natalie Erika James, about a woman on the edge of dementia...

Gloria, a new film from Chile, seemed top be such a simple story that I thought “Why should I see this?” until I finally...