Jean-Luc Godard’s misunderstood antiwar film from 1963 exposes the stupidity of war by ridiculing the aesthetics of war movies.

Jean-Luc Godard’s misunderstood antiwar film from 1963 exposes the stupidity of war by ridiculing the aesthetics of war movies.

The philosopher Simone Weil once remarked that evil is attractive in literature, but ugly and stupid in real life. Les Carabiniers, a 1963 film by French director Jean-Luc Godard, succeeds in portraying this truth. It’s an antiwar film that, instead of evoking indignation—a sentiment that creates a kind of safe zone for the audience—relies on absurdist dramatic methods and sardonic humor to shove the idiocy of war right at us.

Two soldiers arrive at an isolated shack in the middle of nowhere and assault the inhabitants, two men and two women (the exact relationships of the four are never quite clear). When they surrender, the soldiers offer the men a proposition, presented formally in what they refer to as a “letter from the King.” They can join the army and fight for the King, with permission to do whatever they want. (Burn down villages? Yes. Stab people in the back? Yes. Leave a restaurant without paying? Of course. And so forth.) In return they will receive all the treasures of the world. The men agree and the women send them off—one of them asks that they bring her back a bikini.

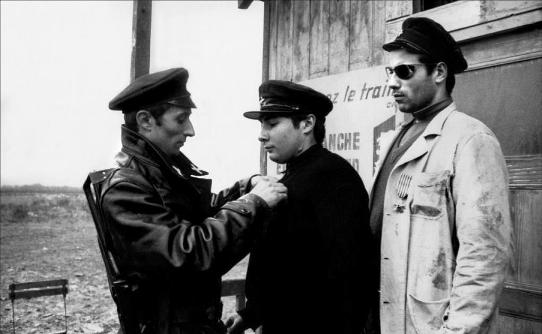

The two recruits (played by Marino Masé and Albert Juross) go off to war. Godard shows them shooting guns, intercut with stock footage from World War II of battles, bombs dropping, etc., and incessant gunfire on the soundtrack. The grainy newsreel-style photography matches the stock footage exactly, but of course the film’s meager budget produces an anti-realist effect, which is amusing and quite effective. The supposed war film is actually a critique of the aesthetics of war films.

Occasional intertitles contain quotes from letters that the boys send home. For example: “Our dedication to the King is such that we are willing to not only shed our own blood, but that of others.” “We leave traces of blood and corpses behind us. We kiss you tenderly.” The mock-heroic style of the intertitles contrasts well with the banal visuals.

The chubby-faced Juross plays a perfect imbecile. At one point he attends the cinema for the first time and ends up destroying the screen trying to peek over the edge of a bathtub in the movie to get a better view of the woman bathing in it. This ties in with one of Godard’s major concerns—image merging with reality.

The actors perform in a casual, make-believe manner, and in fact the film calls attention to itself as “only a movie” as part of its distancing technique. It’s a remarkably intelligent film, disposing of imperialism, war, jingoism, mindless obedience, and the dishonesty of the social order, with an efficiency that is never didactic or overbearing. It is also one of Godard’s funniest works. The outcry when it was originally released was so intense—audiences and critics seem to have felt personally insulted by the picture—that it was withdrawn from theaters and not shown again until 1967, when the political situation had caught up with it. It was ahead of its time, and in a way, it still is.

Les Carabiniers (The Soldiers) is available on DVD.

Emma Seligman’s debut feature uses a shiva, a Jewish post-funeral gathering, as the setting for a comedy about a young woman who doesn’t fit...

Twenty years after the release of Shunji Iwai’s film about early adolescence, the movie’s insights and prescience about the effects of the internet are...

Young men compete in a punishing walking race for which there can only be one survivor, in an adaptation of a Stephen King allegory...